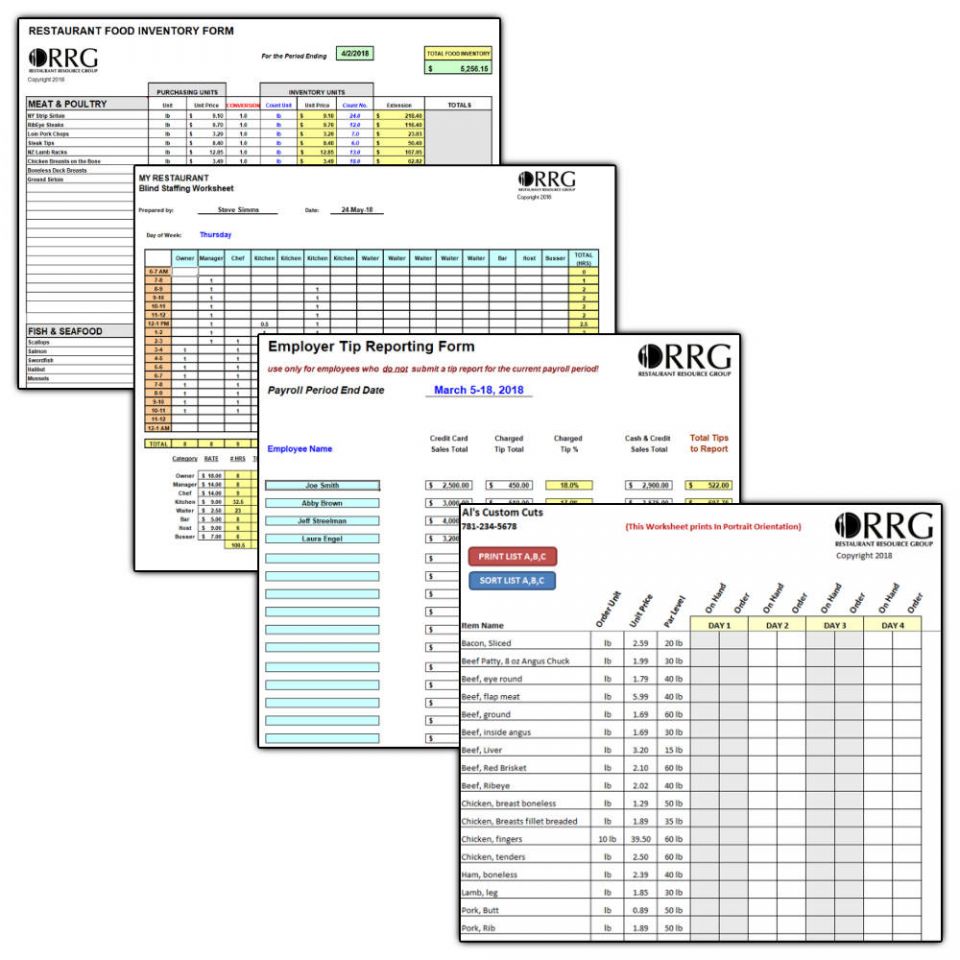

Restaurant

Operations & Management Spreadsheet Library (20)

Our Library of 20

customized Microsoft Excel Spreadsheets are designed specifically for

foodservice applications! They are configured to organize critical financial

information generated by your restaurant on a daily, weekly and/or monthly

basis; to forecast trends and help with budgeting; and even to assist you in

performing many types of "what if" analysis. But that's not

all...many are also designed to make manual entries into your accounting system

more streamlined.

Only $129

Restaurant Rules of Thumb

By Jim Laube, RestaurantOwner.com

The first and most fundamental restaurant rule

of thumb is "every independent restaurant is unique." However, rules

of thumb regarding the financial and operational aspects of restaurants can

provide a valuable starting point for evaluating and understanding the

financial feasibility and performance of proposed and existing restaurants.

Restaurants generate a lot of numbers so

particularly for those new to the industry; deciding what numbers to focus on

first and knowing what they mean can be more than a little perplexing. Rules of

thumb can help operators determine where to look first and what to expect.

This article discusses several of the

restaurant industry's basic rules of thumb. While there will always be

exceptions, they have proven to be surprisingly reliable over the years that I

have worked with operators who collectively manage thousands of diverse

restaurant operations. Keep these numbers handy when planning your restaurant

and assessing your performance after you open.

Investment Rules of Thumb

One of the primary indicators chain operators

use for evaluating the feasibility of a new location is the sales-to-investment

ratio. This ratio compares the projected annual sales of a proposed site with

its estimated startup cost. The ratio looks like this:

Sales to Investment = Annual Sales / Startup Cost

Startup cost includes all the costs necessary

to open the restaurant including leasehold improvements (or land and building),

furniture and equipment, deposits, architectural and design, accounting and

legal, preopening expenses, contingency and working capital reserve.

Sales to investment - Leasehold. When

evaluating the feasibility of a proposed restaurant in a leased space, a rule

of thumb says that the sales-to-investment ratio should be at least 1.5 to 1,

or a minimum of $1.50 in sales should be expected for every $1 of startup

costs. This means that if the cost of opening a restaurant in a leasehold

situation was estimated to be $500,000, the location should be given further

consideration only if the annual sales volume of at least $750,000 could be a

realistic expectation.

Sales to investment � Ownership of land and

building. The rule of thumb for restaurant

projects in which the operator owns the land and building calls for a

sales-to-investment ratio of at least 1 to 1, or $1 in sales for every dollar

of startup costs.

While there are many other considerations in

deciding whether to open in a particular location, this is one ratio that many

operators use as an early indicator of whether to move on to other factors in

the go/no go decision process.

Profitability Rules of Thumb

Sales per square foot. While

not all high-volume restaurants make lots of money, they do have the greatest

opportunity to generate a sizable amount of profit. Sales volume is the most

reliable indicator of a restaurant's potential for profit and a useful way to

look at sales volume when evaluating profit potential is through the ratio of

sales per square foot.

It's easy to calculate a restaurant's sales

per square foot. Just take annual sales and divide by the total interior square

footage including kitchen, dining, storage, restrooms, etc. This is usually equal

to the net rentable square feet in a leased space. The ratio looks like this:

Sales per Square Foot = Annual Sales/Square Footage

In most cases, full-service restaurants that

don't generate at least $150 of sales per square foot have very little chance

of generating a profit. For example, a 4,000-square-foot restaurant with annual

sales of anything less than $600,000 would find it very difficult to avoid

losing money. This works out to $50,000 in monthly and $12,000 in weekly sales.

Limited-service restaurants that generate any

less than $200 of sales per square foot have little chance of averting an

operating loss. Industry averages reveal that limited-service restaurants tend

to have slightly different unit economics than their full-service counterparts.

Higher occupancy costs (on a per-square-foot basis) and lower check averages

are two of the primary reasons for this difference.

At sales levels of $150 to $250 per square

foot (full-service) and $200 to $300 (limited-service), restaurants with effective

cost controls may begin to approach break-even, with some well-managed

operations able to achieve a net income of up to 5 percent of sales.

At sales levels of $250 to $325 per square

foot (full-service) and $300 to $400 (limited-service), restaurants may see

moderate profits, which are defined as 5 percent to 10 percent net income

(before income taxes) as a percentage of total sales. Generally, you don't

want management salaries to exceed 10 percent of sales in either a full- or

limited-service restaurant. This would consist of all salaried personnel.

High profit can be defined as sales levels

more than $350 per square foot (full-service) and more than $400

(limited-service). Generating sales at these levels affords the opportunity for

some operators to generate a net income (before income taxes) in excess of 10

percent of sales.

There are many factors that influence a

restaurant's profitability besides sales volume. Two of the biggest are prime

cost and occupancy costs. Without competent management and effective systems

and controls over food, beverage, labor and other operating expenses, no amount

of sales will produce much more than mediocre operating results.

Likewise, occupancy costs, which are not

controllable by restaurant management, will have a significant effect on

profitability. The sales volume rules of thumb above assume an "industry

average" occupancy cost from $15 to $22 per square foot. If your occupancy

costs are higher than $22 per square foot, the sales numbers above will be low

when using them to evaluate your restaurant's profitability.

Percentage of Cost Rules of Thumb

Food cost. Food

cost as a percentage of food sales (costs/sales) is generally in the 28 percent

to 32 percent range in many full-service and limited-service restaurants.

Often, more upscale full-service concepts, particularly those that specialize

in steaks and/or fresh seafood can have food cost of 38 percent, 40 percent and

even higher. Conversely, I'm familiar with some gourmet pizza restaurants in

upscale areas that are able to consistently achieve a food cost of 20 percent

and sometimes even less. Some people might be surprised that some of the most profitable

restaurants in our industry have a food cost in excess of 40 percent.

Alcoholic beverage costs. Alcohol

costs vary with the types of drinks served. Among the reasons that bar service

is so desirable are both the relative profitability of alcohol and the ability

to control costs, as long as servers are trained to pour accurately, and theft

is not a significant problem. Below are typical costs in percentages:

� Liquor - 18 percent to 20 percent.

� Bar consumables - 4 percent to 5 percent as a

percent of liquor sales (includes mixes, olives, cherries and other food

products that are used exclusively at the bar).

� Bottled beer - 24 percent to 28 percent

(assumes mainstream domestic beer, cost percent of specialty and imported

bottled beer will generally be higher).

� Draft beer - 15 percent to 18 percent

(assumes mainstream domestic beer, cost percent of specialty and imported draft

beer will generally be higher).

� Wine - 35 percent to 45 percent (the cost percentages of

wine can vary dramatically from restaurant to restaurant depending primarily on

the type of wines served. Generally, the higher the price per bottle, the higher

the cost percentage).

Non-alcoholic Beverage costs. It

is standard industry practice to record nonalcoholic beverage sales and costs

in Food Sales and Food Cost accounts, respectively:

� Soft drinks (post-mix) - 10 percent to 15 percent

(another rule of thumb for soft drinks is to expect post-mix soda to cost about

a penny an ounce for the syrup and CO2).

� Regular coffee - 15 percent to 20 percent

(assumes 8-ounce cup, some cream, sugar and about one free refill).

� Specialty coffee - 12 percent to 18 percent

(assumes no free refills)

� Iced tea - 5 percent to 10 percent iced

tea is the low food cost champ of all time. Cost of the tea can be less than a

penny per glass. Biggest cost component in iced tea is usually the lemon slice.

Paper cost. In

limited-service restaurants paper cost should be classified as a separate line

item in "cost of sales." Historically, paper cost has run from 3

percent to 4 percent of sales. However, the recent run-up in the cost of many

paper goods has increased the paper cost percentage to more than 4 percent of

sales in many restaurants. In full-service restaurants, paper cost is usually

considered to be a direct operating expense and normally runs from 1 percent to

2 percent of total sales.

Payroll

and Salaries. Payroll cost as a percentage of sales includes

the cost of both salaried and hourly employees plus employee benefits, which

includes payroll taxes, group, life and disability insurance premiums, workers'

compensation insurance premiums, education expenses, employee meals, parties,

transportation and other such benefits. Total payroll cost should not exceed 30

percent to 35 percent of total sales for full-service operations, and 25

percent to 30 percent of sales for limited-service restaurants.

Generally, you don't want management salaries

to exceed 10 percent of sales in either a full- or limited-service restaurant.

This would consist of all salaried personnel including general manager,

assistant manager(s), chef or kitchen manager.

One caveat on this would be in a situation in

which a working owner fulfills the role of the general manager and/or chef and

takes a salary in excess of 3 percent to 4 percent of sales. When this occurs,

management salaries can easily exceed 10 percent of sales and total payroll

cost can appear excessive as well.

Hourly Employee Gross Payroll

� Full-service Restaurant - 18 percent to 20 percent

� Limited-service Restaurant - 15 percent to

18 percent

Limited-service restaurants generally have

lower hourly payroll cost percentages than full-service restaurants. In

limited-service restaurants, managers often perform the work of an hourly

position in addition to being a manager. In some cases, however, hourly workers

may also perform management roles on some shifts, which could lead to higher

hourly payroll costs in these restaurants.

Employee Benefits

� 5 percent to 6 percent of total sales

� 20 percent to 23 percent of gross payroll

Employee benefits can vary somewhat depending

primarily on state unemployment tax rates and state workman's compensation

insurance rates. California, for example, has had for the past several years

very high workers' compensation premium rates as compared with rates in other

states. Restaurants that are new or have had a large number of unemployment

claims may have state unemployment tax rates that could cause their employee

benefits to be higher than the rules of thumb above.

Prime Cost Rules of Thumb

Prime cost is one of the most telling numbers

on any restaurant's profit-and-loss statement. Prime cost is arrived at by

adding cost of sales and payroll costs. Prime cost reflects those costs that are

generally the most volatile and deserve the most attention from a control

standpoint. It's very easy to lose money due to lax or nonexistent controls in

the areas of food, beverage and payroll. Many successful restaurants calculate

and evaluate their prime cost at the end of each week. In the chart, if total

sales were $60,000, then prime cost would be running $39,100 or 65 percent of

sales.

Prime Cost

� Table-service - 65 percent or less (total

sales)

� Limited-service - 60 percent or less (total sales)

As prime cost exceeds the above levels it becomes increasingly difficult to

achieve and maintain an adequate bottom-line profit in most restaurants. When

looking at a restaurant's overall cost structure, prime cost can be very

meaningful, particularly in cost of sales and payroll cost. Some restaurants,

such as steak and seafood restaurants, may carry very high food cost and yet be

extremely profitable. Again, this can be exhibited by looking at prime cost.

People might be surprised that some of

the most profitable restaurants in our industry have a food cost in excess of

40 percent. I'm familiar with a seafood restaurant outside of a major Midwest

city that, according to reliable sources, consistently operates with a food

cost of 45 percent or higher, which is not all that uncommon in restaurants

specializing in high-quality steak and/ or seafood.

You might be thinking, though, how any

restaurant could make money let alone be highly profitable when its food cost

gets close to 50 percent of sales. Well this particular restaurant does more

than $20 million in annual sales in about 20,000 square feet. This means that

its sales are more than $1,000 per square foot, which is among the highest in

the industry.

Even though their food cost is as high as say

45 percent, what do you think their labor cost is as a percentage of sales when

they generate a sales level this high? I'm fairly certain it's much lower than

the industry average, which is around 30 percent to 35 percent. In fact, their

payroll, including management, hourly staff and taxes and benefits is probably

around 15 to 18 percent of sales, but let's say it's 20 percent to be

conservative.

Let's also assume that their sales mix is 85

percent food and 15 percent liquor, beer and wine. If their combined beverage

cost is, say, 25 percent of beverage sales. If our assumptions about beverage and payroll

costs are fairly accurate, you can see that its prime cost is well below the 65

percent threshold. This means that even with a very high food cost, this

particular restaurant should be very profitable, assuming its remaining costs

and expenses are in line with restaurant industry averages.

Some restaurants, like many ethnic concepts,

have relatively low food costs, with some well under 30 percent of sales. You

might think that these restaurants would be extremely profitable. They might

be, but often these restaurants have lower check averages and are more labor

intensive, so their payroll costs are much higher as a percentage of sales

than, say, a steak or seafood restaurant.

Looking at cost of sales and payroll costs

together as prime cost usually provides a much more meaningful and valid

indication of a restaurant's cost structure and potential for profit.

Rent and Occupancy Cost Rules of Thumb

Rent (6 percent or less). Rent used here is the ongoing payments made by an operator to the lessor for the use of premises. Rent payments may be fixed or based on a percentage of sales. Generally, the goal is to limit rent expense to 6 percent of sales or less, exclusive of related costs such as common area maintenance (CAM) and other occupancy expenses.

Occupancy cost (10 percent or less). Occupancy

cost includes rent, CAM, insurance on building and contents, real estate taxes,

personal property taxes and other municipal taxes. Many operators want to keep

occupancy cost at or below 8 percent of sales, however, 10 percent is generally

viewed to be the point at which occupancy cost starts to become excessive and

begins to seriously impair a restaurant's ability to generate an adequate

profit.

Sales Value of Restaurant Business Rules of Thumb

Accurately determining the potential sales

value in any restaurant requires the services of a professional business

appraiser, preferably with experience appraising independent restaurants.

However, there are two rules of thumb that may

be helpful to arrive at an initial, rough estimate of what your restaurant may

be worth, assuming you operate in leased space:

�

Sales value of business (gross sales method) - 38 percent to

42 percent of gross sales.

� Sales value of business (cash flow method) - annual cash flow (basically net income before depreciation, debt service and owner compensation) times a multiple of three to four.

When determining the value of a restaurant in leased space, one of the most important determinants is the terms, particularly the transferability and the amount of time, with options, remaining on the existing lease. Lease factors such as these and other terms can have a significant effect on the value of any business.

In restaurants where the operator owns the

land and building, the inherent value of the business will be influenced

significantly by the underlying value of the real estate. For this reason it is

difficult to value the business in a meaningful way using rules of thumb.

Final Rule of Thumb: Not Every Rule of Thumb Fits Every

Restaurant

Most restaurants will probably deviate from

one or more of the rules of thumb discussed in this article. That's to be

expected. Rules of thumb, as discussed above, are merely guidelines, not an

ironclad collection of industry mandates from which no successful restaurant

can deviate.

Where your numbers do stray from these norms,

it may be useful to determine "why." Determining the reasons for any

differences may prove to be an insightful process in learning more about the

financial and operating nuances of your restaurant.

Another rule of thumb says that the more you

understand how your restaurant works, the better the manager you will become.

Using these rules of thumb could go a long way in helping to better understand

your restaurant and provide insights for building a more successful business.

At a Glance: Rules of Thumb

Sales to Investment (Annual Sales/Startup Cost)

�

Leasehold - at least 1.5 to 1.

�

Own land and building - at least 1 to 1.

Sales Per

Square Foot

�

Losing Money Full-service - $150 or less.

Limited-service - $200 or less.

�

Break-even Full-service - $150 to $250. Limited-service -

$200 to $300.

�

Moderate Profit Full-service - $250 to $350.

Limited-service - $300 to $400.

�

High Profit Full-service - More than $350. Limited-service

- More than $400.

Food Cost

�

Generally - 28% to 32% as a percentage of

total food sales.

Alcoholic Beverage Costs

�

Liquor - 18% to 20% as a percentage of liquor sales.

�

Bar consumables - 4% to 5% as a percentage of

liquor sales.

�

Bottled beer - 24% to 28% as a percentage of

bottled beer sales.

�

Draft beer - 15% to 18% as a percentage of

draft beer sales.

�

Wine - 35% to 45% as a percentage of wine sales.

Nonalcoholic

Beverages

�

Soft drinks (post-mix) - 10% to 15% as a

percentage of soft drink sales.

�

Regular coffee - 15% to 20% as a percentage of

regular coffee sales.

�

Specialty coffee - 12% to 18% as a percentage of

specialty coffee sales.

�

Iced tea - 5% to 10% as a percentage of

iced tea sales.

Paper

Cost

�

Full-service - 1% to 2% as a percentage of

total sales.

�

Limited-service - 3% to 4% as a percentage of

total sales.

Payroll

Cost

�

Full-service - 30% to 35% as a percentage of

total sales.

�

Limited-service - 25% to 30% as a percentage of

total sales.

Management Salaries

�

10% or less as a percentage of total sales.

Hourly Employee Gross Payroll

�

Full-service - 18% to 20% as a percentage of

total sales.

�

Limited-service - 15% to 18% as a percentage of

total sales.

Employee

Benefits

�

5% to 6% as a percentage of total sales.

�

20% to 23% as a percentage of gross payroll.

Prime

Cost

�

Full-service - 65% or less as a percentage of

total sales.

�

Limited-service - 60% or less as a percentage of

total sales.

Occupancy

and Rent

�

Rent - 6% or less as a percentage of total sales.

�

Occupancy - 10% or less as a percentage of

total sales.